School Ties

Student life at Rosary does not resemble the care-free school days I remember. Breakfast is at 7:15am - a cup of coffee and a scone. Class all morning until lunch at 12:40 - boiled kau kau and another scone. Schoolends at 3:10. Then the students (on a rotating schedule) perform community service - gardening and farming the school grounds. I do not know what these chores have to do with community service. Dinner is at 5:30pm - kaukau, greens, scone and tinned fish. No one is able to talk about the mess hall without a grimace. There are some things you cannot 'unsee'. I dare not walk into the building. Night study begins at 6:30pm and runs to 9pm -2 ½ more hours, stuck in a classroom after they have been in one all day. Lights out at 10pm.

The days start early on the weekends as well. More community service, more study time, community mass and even a section called 'quiet time'. The kids do get to play sports on the weekends and it is a necessary release. I'm surprised they don't kill each other on the playing fields. They are in the middle of a vast valley yet are confined to stuffy classrooms all day long. Then again, I imagine that most boarding schools around the world mirror a similar schedule.

Most students are under serious pressure from their families and communities to perform well in school and to move on to tertiary-level education. In some cases, the entire village has contributed to the school fees. The student is seen as an investment. If the child moves on to college and gets a white-collar job, they can kick back a portion (usually a hefty one) of their earnings to the family. If the student returns home they are seen as a failure. These expectations are largely unfair. There are few, high-paying jobs and the number of available slots (more Secondary schools, same number of universities/technical colleges) in college drop by the day. Over 80% of the students at Rosary used to move on to tertiary level education. That figure has dipped below 50% and continues to fall.

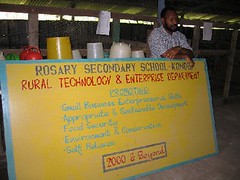

While the opportunities to receive higher education have fallen, parents' expectations have not. Schools are trying to adjust to this trend by offering more 'relevant' subjects - a move supported by the Department of Education. Practical skills, such as farming and carpentry are being introduced in order to prepare the growing number of students that will return to their villages. This shift has not been embraced by the families paying the school fees. They are clinging to the belief that a school should prepare their children for university. They don't want their child wasting time in a farming class when they could be preparing for the national mathematics exam. It's a challenging dichotomy.